[Digital Poetics 4.17] Sweat And Stress: On Timothy Thornton’s “Shapeshifting” by Luke Roberts

Timothy Thornton, Shapeshifting (London: RunAmok, 2024)

In autumn last year I gave a reading in a bookshop in Massachusetts. It was a couple of months after my father died, and the invasion of Gaza was just beginning. I felt overwrought, a long way from home, pummelled by grief and loss. But browsing the bookshelves before the reading began, I was surprised to find something I’d helped publish back when I was in my early twenties: a copy of Timothy Thornton’s Jocund Day (2011). It’s an oversize pamphlet, white card, royal blue discus on the cover. Because it was on the bottom shelf I literally fell to my knees to retrieve it. This precious relic would protect me, bring me luck.

If you don’t know it, Jocund Day is one of the great sequences of whatever era that was. It’s an audacious book, full of sex and music, quarries and canals, shoulders and tattoos. The poems have titles like ‘Cairn-Punching’ and ‘Hunting Tungsten Out’. In the circles I moved in it was considered a classic even before it had been published. Tim would give readings from it in progress and our language would expand with the joy and colossal sadness of it. Maybe because of his background as a pianist and composer, his technical control of the poem’s music put most of us to shame. Who was this guy with the shaved head and doc martens, talking about obscure Elizabethan song and doing wild intricacies with words like gull and hector and gantry?

Several pamphlets have followed since, and in retrospect Tim’s work clearly heralded the emergence of a new tendency of queer experimental poetry. This synthesised and swerved a number of influences around the poetry scenes of Cambridge, Brighton, and London, and added a raft of co-ordinates that fundamentally altered the landscape. In Trails (2011) and Working Together For a Safer London (2014) the work took a satirical turn, with gleeful and venomous send-ups of the culture of the English ruling class during the era of mass protest and riot. In Water Effects Burning On/Off (2016) and Nothing Worked (2021) the register is more fragile and despairing, shattered by the cumulative barbarity of austerity.

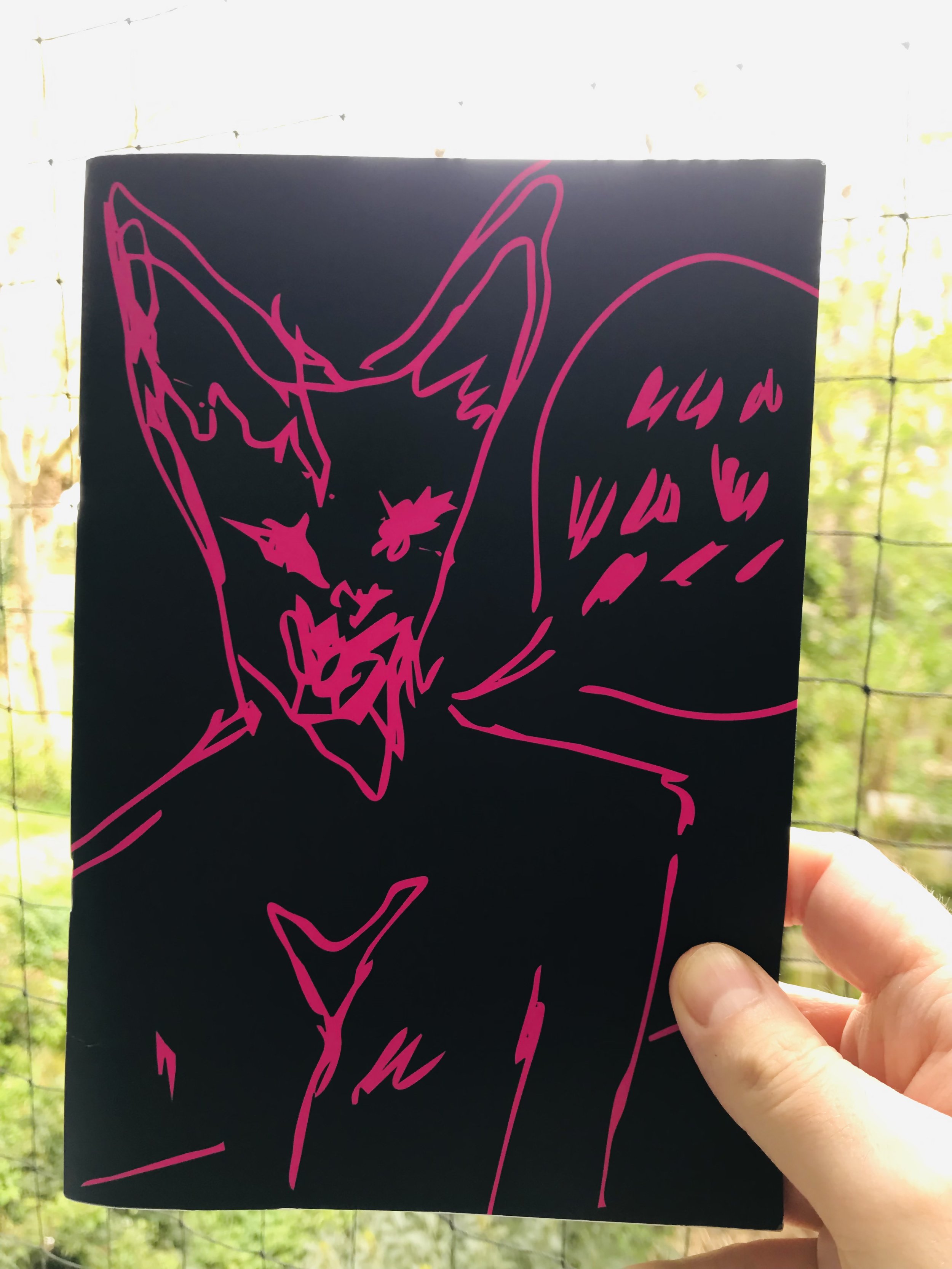

But the point of this prelude is to say that Shapeshifting (2024), right out of the blue, is a work of startling beauty and tenderness. There are 28 poems, mostly with one-word titles, plus some scratchy drawings to complement the cover by Salomé Honório. The structure seems to call back to Jocund Day, a set of love lyrics with distinct motifs, prized words (hector, again! lozenge!), and a settled devastation of style. These are poems of loneliness and sudden, frantic encounter. They tend towards cliff edges, ridges, caves, towpaths, woods. Thornton is a great poet of setting out, and the boyish entanglement of utopia and panic. ‘We should go!’, he once wrote, and as readers we try to keep up, conscious of the depth of the water, the strength of the current, the suddenness of the drop.

Thornton’s great predecessor is Gerard Manley Hopkins, and the way Hopkins – verbally, musically – can both grasp a whole field and zero in on the particular glint of a body in flight, always thrilling at the linebreak. It’s not easy to excerpt, but in what I think starts out as a description of a waterfall Thornton writes:

Love-duets down and what it is like is it is like

it is breathing an explosion of free unimpededSnow as reflects lightnings of sweat and stress

deformed oblong chamber in a sawn-openNautilus shell

comic-strip

panel wobbling

Part of the excitement of this poetry comes from the process of tripping up and recovering our breath. Promiscuous simile unspools, and the nouns are unsteady footholds. What’s the relationship between ‘snow’, ‘sweat’, ‘the deformed oblong chamber’ and the ‘sawn open /Nautilus shell’? The line-serrations mean we can separate the units of sense for inspection, but this doesn’t account for their contradictory energies when we restore them to the circuit of syntax. Is the poem like a comic-strip panel wobbling? Or is it more like a sawn-open nautilus shell? Neither image wholly resolves, buzzing with interference at the edge.

The sequence has a loose narrative hook in the form of two figures, Jackdaw and Icarus, who don’t quite meet. Each carries some symbolic freight. Icarus, of course, is heedless and headstrong and tragic. In Aesop’s telling, the envious Jackdaw sees an Eagle carrying away a lamb in its mighty talons. Attempting the same trick, the Jackdaw gets tangled in the lamb’s wool, and has its wings clipped by a shepherd. So perhaps rather than characters these are positions the poem navigates: the flight upwards and the swoop to earth, the weight of the self and the weight of what we want. There are other figures: the Boxer, whose name is J––– (short for Jackdaw?), and who fucks I (short for Icarus?) beneath a bridge and a lighthouse, and is fucked beneath a phone-mast and a pier.

One of the strengths of Thornton’s work is that the objects, images, and words his poems gravitate towards are not generic bearers of expected recognition, but seem instead to be deeply personal, full of private erotic charge and intensity. If he wanted to, I’m sure Thornton could write poems of rather slick description, complete with brief flickers of estrangement and return to safe ground. But these poems aren’t like that. They attempt feats of intimacy and recovery that can only break off in stunned wonder: ‘Hurt and fear toppling / Into this silence I flicker forward suddenly’; ‘Our delirium has this fervent grain or burr to it’; ‘Is it now we are droplets in the dark’. The very last poem of the sequence ends with a rare full-stop:

Watch easily how

What remains is joy: theirs alone in dusk

And seaweed and hiding, each a high Icarus bolting in time.

We’re almost caressed, finally, by ambiguity. To bolt is to go; to bolt is to keep in place. It’s the poem that aches with this, the actual language rather than its referent. Maybe this time it will be different, and the deep shadow of mortality that hovers always in the wings would instead offer protection, ‘holding them / Nakedly here forever again’.

Malcolm Cowley once wrote that Hart Crane’s best poems were animated by nothing but ‘proper glitter and violence’. I can’t remember now if he was being wholly complimentary. But I am being wholly complimentary when I say that Timothy Thornton’s work brims over with proper glitter and violence. Line after line shimmers with vicious brilliance:

A naked lentil of pure

Sun reflected imperatives

Out to newly scattered shipsOn the sugary bolt of the sea

Always so derangedly will the gone

Stars fortify again the poetryOf children, and the oats and green

Talons of the countryside

Here’s the bolt again, ‘sugary’, with the sea too bright to look at, and the little rhyme of ‘on’ and ‘gone’ as the point the poem turns around. This is the exacting and costly work of thought and feeling’s transformation into art, sounding it out, sweating over the poem as a site of charged contact and life-preserving song. I’m so glad it’s here.

Luke Roberts

Easter Monday 2024

*

Luke Roberts is the author of Home Radio (2021) and other works of poetry. His critical study, Living in History: Poetry in Britain, 1945-1979 is forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press. He lives in London.